Reverend Edwin King

At great personal risk, Reverend Ed King agreed to run for lieutenant governor in 1963 as Aaron Henry’s running mate. He accepted the role reluctantly, still recovering from wounds suffered in a June car crash in which he and John Salter had been forced off the road. The Vicksburg native’s activism extended back to his student days at Millsaps College in 1958. As Tougaloo College chaplain, King joined Medgar Evers and John Salter in the Jackson Movement. He and his wife, Jeannette, transported Tougaloo students to the March on Washington at a time when sharing a car with Black people put them at risk. King also worked to desegregate Jackson’s White churches. For his activism, King became estranged from his parents and colleagues in the clergy. His parents felt compelled to leave the state.

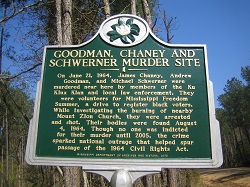

Highlights places and people who fought for freedom and equality in Neshoba County

Highlights places and people who fought for freedom and equality in Neshoba County Museum dedicated to Fannie Lou Hamer and other civil rights heroes

Museum dedicated to Fannie Lou Hamer and other civil rights heroes