Margaret Walker

In words and deeds, Dr. Margaret Walker inspired Black people to learn their own history and determine their own future. An English professor at Jackson State College from 1949 to 1979, Walker’s breakthrough poem—For My People (1937)—portrayed the pain of Black daily life while celebrating strengths. In 1966, Walker published her signature novel, Jubilee, based on the life of her grandmother. Jubilee tells the African American story from slavery through the Civil War and Reconstruction. In 1968, Walker founded the Institute for Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People (now the Margaret Walker Center) at Jackson State University, where she served as director.

First Catholic Church in Mississippi River Valley with exclusively African American congregation

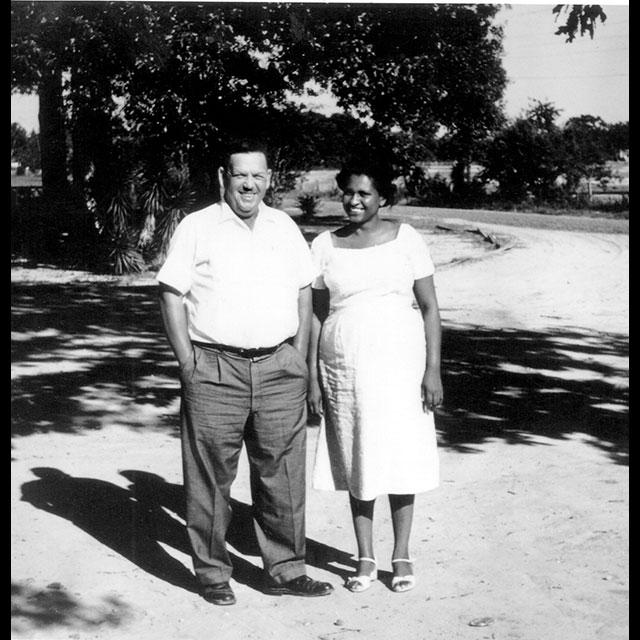

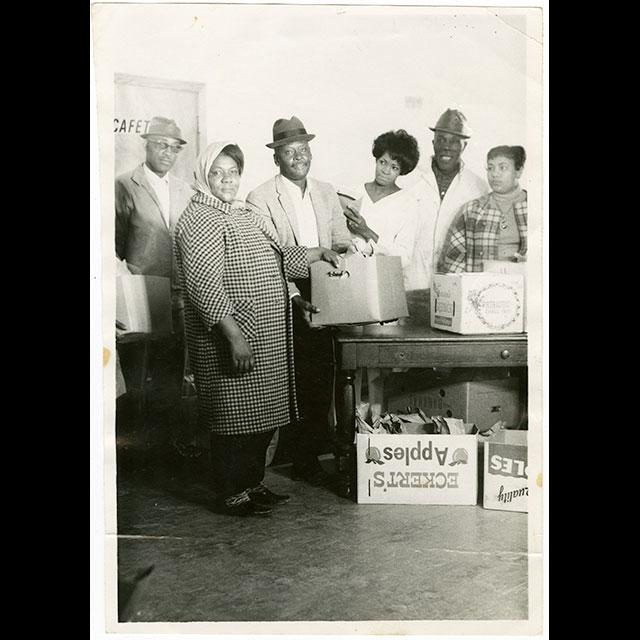

First Catholic Church in Mississippi River Valley with exclusively African American congregation Dedicated to the memory and legacy of famed civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer

Dedicated to the memory and legacy of famed civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer